Akas pygmy men spend a lot of time with their children. The attention and affection they show them, as well as the way they bring them up, are unique. Economic and environmental challenges, however, threaten the way of life of these people.

The afternoon sun slips behind the tall trees that populate the Dja River Biosphere Reserve in southern Cameroon. It fades into patches of deep red, orange and purple. Hundreds of birds emit their last chirps before taking refuge in their nests. In the distance, the cries of monkeys and the bellowing of some other animals.

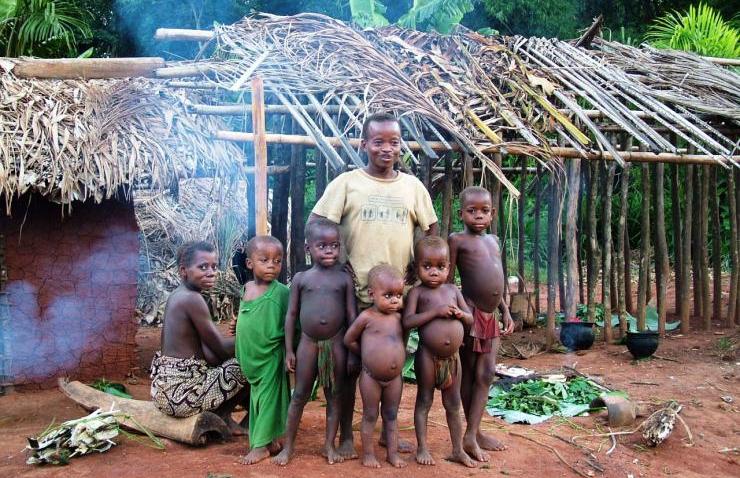

The humid and unrelenting heat of the day gives way to a light breeze that brings relief. Along rainforest paths, young people return to their huts with containers full of matango, a palm plant. They are the last to return home. Before them, women, men and children have returned to their villages, finishing the day’s work. In Ndjibot, the smoke rising through the palm leaf roofs covering the huts suggests that dinner will soon be ready.

Meanwhile, in a corner of the village, a group of men are sitting on logs that serve as benches. Most of them have a little boy or girl in their arms. They talk to each other, discuss the day’s events and laugh. The little ones who are already independent play nearby. They run, chase each other, scream. They give the impression of not bothering anyone.

Men with children in their arms are not the most common sight in many parts of Africa, although times are changing, especially in cities. Normally, in most African villages, there is a division of labour and tasks between males and females.

Taking care of the house and children is always the responsibility of the women. Women are usually responsible for the nutrition, health, education and well-being of children. They are the ones who carry them in their arms, on their shoulders or their hips, while carrying out any daily task, be it fetching water, cooking or working in the fields.

However, things are very different among the pygmy people. They are characterized by a society in which men and women are equal and share all tasks. The inhabitants of Ndjibot are Bakas, one of several pygmy groups that populate the Congo River basin. For generations, like the rest of the population, they have developed their way of living in harmony with the forest, which they consider divine.

They take care of it and preserve it. For this reason, they only hunt what they can eat and share the fruits and roots they collect with other members of the group. The jungle provides them with everything they need to live and there is no need to hoard or conserve. They are semi-nomadic and follow the cycles of animals or plants.

Traditionally they are organized in small groups, with monogamous marriages and open nuclear families. Children are free and fend for themselves; there is divorce and the elderly are the authorities. Most jobs are not limited to one genre or another; everyone is involved in everything: hunting, fishing, gathering. They also differ from other peoples in that children are treated and valued equally.

Pygmy groups have non-authoritarian leaders. They use their wisdom only to advise, but each individual is free to make their own decisions. Among forest dwellers, nothing is more respected than personal autonomy. Pygmy society is therefore very egalitarian: only knowledge and competence are valued. The master hunter – the tuma – and the medicine man – the nganga – gain prestige and recognition when they reach that level, but never authority over the rest of the village. Important decisions that affect everyone are made by consensus and involve both women and men.

This lifestyle is also reflected in the education of younger children. Armand Faya says he doesn’t know why he is holding his daughter, “It has always been like this. We all take care of each other. Children are precious, they are our future, a gift from God. This is why we protect them, and we take care of them until they start to fend for themselves.

Things are changing and the life of the Pygmies is slowly and inexorably changing. For years, in fact, the governments of the various countries bordering the Congo River basin have forced them to leave the forest in which they have lived all their lives and to settle along the roads.

In this way, rulers have a free hand to usurp the lands these people once roamed freely and hand them over to logging or mining companies, mostly foreign. The rest is transformed into agro-industrial farms and agricultural land for the non-pygmy population or large multinationals. Or in reserves and natural parks from which they were expelled where they could neither hunt nor practice their traditional lifestyle.

The Pygmies have been forced to become sedentary. This has had many negative consequences for them, bringing some groups, such as the Bayeli, to the brink of extinction. This community, living near the Kibri region of Cameroon, has been driven out of its natural environment to make room for planting large areas of oil palms. Without forests and rivers, they threw in the towel and sank into depression. Alcoholics without a future, the Bayeli are destined to disappear. One of the clearest symbols of change is represented by houses. The traditional one, the mongulu – a sort of igloo made of branches and leaves – was erected in a couple of days. They were easy to abandon when the family moved elsewhere and easy to rebuild when they returned a few months later.

Now they have been replaced by rectangular mud buildings with palm leaf roofs, like those of the villages in the area where they were forced to settle. These are permanent structures, meaning they no longer move through the jungle following animal tracks or plant cycles, as they have done for generations. This is not just an aesthetic change but something deeper. The women built the Mongols, while the men went into the forest to look for branches and sticks. Now mud houses are men’s work and women are not assigned to this work.

At most they transport construction materials. By doing so, they gradually lost control over the family residence and so, little by little, women see the mechanisms of social power that they traditionally exercised over men, and which allowed them to interact on equal terms with them disappear. This is just the tip of the iceberg.

Assimilation by the peoples with whom they are forced to share road space is introducing new customs that always work to the detriment of women, as in the case of marriage dowry.

“Before, it didn’t exist”, explains Faya, “but now parents, copying the Bantu, ask for it. It’s usually around 50,000 CFA francs (76 euros), plus food, machetes, clothes and household goods. It’s too much. If a man ‘buys’ a woman with a dowry since money is not easy to collect and involves a lot of effort in which the groom’s entire family is involved, he will consider her as his personal property and not his equal, as was the rule among the pygmy peoples. This results in other problems such as gendered violence, rape and polygamy, which were previously practically unknown. Likewise, the division of labour between males and females is gaining ground.

All these attitudes are becoming normalised as a direct consequence of the disruption of the balance that once prevailed in the Pygmy culture. Young people also imitate their neighbours in the way they dress, their hairstyles, their cell phones, headphones and motorbikes, for those who can afford them, imitating any other young people of their age.

They no longer live in the jungle; they have settled down and adopted new customs. The only thing that seems to have survived the degradation of the Pygmy culture is their parenting style. Parents still take care of their children, playing with them, carrying them, feeding and washing them. Moïse Toixton lives in the village of Namikumbi, sitting on a log, playing with his five-year-old son, Dany. He tickles him. The child laughs. It’s true, that there are things which, despite external threats, do not change. The little ones are still considered a blessing and are loved by all the members of the group.

(Chema Caballero)