In all religions, we find cities called “holy” due to the presence of the supernatural within their walls. We can mention Jerusalem for Christians and Jews, Mecca and Medina for Muslims, Benares for Hinduism and Sarnah for Buddhism in India, etc. But Timbuktu is called holy by the sages and believers who have lived there throughout history. This is why Timbuktu bears the title “The City of 333 Saints”

Set in the vastness of Mali’s Sahelian desert, Timbuktu has been a religious, cultural and commercial centre for more than 600 years, whose residents have travelled throughout Asia, Africa and Europe, and the birthplace of great Muslim masters, known throughout the Islamic world.

On the other hand, in the 14th century, it was considered the richest city in the world for its salt and gold reserves, as well as being an academic destination of the Muslim world for its libraries and schools. Located south of the Sahara Desert and 13 kilometres from the Niger River, Timbuktu was declared a World Heritage Site in 1988. But its history began much earlier, in the year 1100, as a temporary camp for Tuareg nomads at the point where the desert meets the water at the bend of the Niger River, becoming an important centre of trade.

In the 13th, 14th and 15th centuries, Timbuktu experienced a great period of commercial development and Muslim culture. Three of its great mosques, Djingerber, Sankore, and Sidi Yahia, were built in those centuries, and by 1450 it had a population of 100,000 with 25,000 Muslim scholars who had studied in Mecca or Egypt. In 1468, Timbuktu was conquered by the Songhai, and in the following years until 1591 it became important as an academic centre and one of international trade in gold, slaves, salt, cloth and horses from North Africa.

Conquered by Morocco in 1591, which persecuted the religion but defended it militarily. The city was subsequently attacked and conquered by the Bambara, the Peul and the Tuareg. France conquered it in 1893, making a great effort to repair its historic buildings. Since 1960, Timbuktu has been part of the newly independent state of Mali. For centuries, non-Muslims were banned from entering the city.

The first European to enter the city, it is said, was Leo Africanus, a Muslim from Granada in the first half of the 16th century, who accompanied his uncle on a diplomatic trip. European explorers became interested in Timbuktu in the 19th century. The best known is the French explorer René-Auguste Caillié. Caillié, who had studied Arabic and Islam, arrived in the city disguised as an Arab in 1828 and after two weeks’ stay left, writing a diary of his impressions. Later, in 1892, the German geographer Heinrich Barth arrived on his five-year trip to Africa.

The city flourished in the 16th century, becoming an Islamic centre and home to scribes and jurists. For experts, “Timbuktu’s most famous and lasting contribution to Islamic and world civilization is the scholarship practised there: the spiritual centre of Islam in the 15th and 16th centuries with its Sankore University, where important books were written and copied, making the city the centre of a significant written tradition in Africa.”

The teaching, in Arabic, was aimed at the Muslim religion, but linguistics, literature, Greek philosophy, geography, law and medicine, in particular eye surgery, were also taught. At the height of its heyday, “learned Moors expelled from Spain and Moroccan intellectuals did not hesitate to settle in Timbuktu”, near the banks of the Niger River, and exchanges with foreign universities such as Cairo and Damascus multiplied.

Becoming an international centre of culture, the number of schools grew to 180 with 20,000 students in a population of 80,000. At the end of the period of its greatest splendour, Timbuktu entered a long-lasting dream that still endures today.

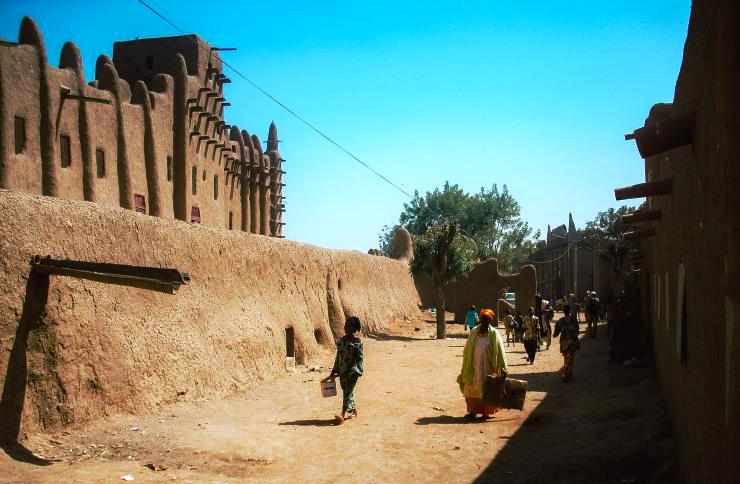

Today, Timbuktu has a population of 55,000 (2009 census) and the most widely spoken language is a variety of Songhai, although Hassaniya Arabic and Tamashek are spoken by the minority. Timbuktu is the administrative centre of the region. Its streets are sandy, dusty, narrow and winding; its historical monuments are threatened by the proximity of the desert, the advance of the dunes and desertification.

The Islamic militants – in particular, one group known as Ansar Dine – deemed many of Timbuktu’s historic religious monuments and artefacts to be idolatrous, and, to that end, they damaged or destroyed many of them, including tombs of Islamic saints housed at the Djinguereber and Sidi Yahia mosques. Work to repair the damage began after the militants were routed from the town in early 2013.

What should we remember about this city so rich in history? The three great mosques: The Djinguereber Mosque built in 1325 by Abu Isha-qes-Saheli, an architect from Granada, under the patronage of Emperor Kanga Musa, with the capacity to accommodate ten thousand faithful. The Sankoré Mosque, built in the 15th century, was once an important Madrasa or university of Islamic sciences. The Sidi Yaya Mosque, built in 1440, with a door that could only be opened at the end of time. The mausoleums and tombs of the saints: there are 22 mausoleums of Muslim “saints” in Timbuktu, of which sixteen are part of the world heritage. The best known are those of Sidi Yaya and Sidi Mahmoud, destroyed by terrorists in June 2012. Manuscripts: It is estimated that around 100,000 manuscripts are preserved in the “Ahmed Baba Documentation and Research Centre”, founded in 1970, and in the homes of some families of the city.

At the end of September 2003, the construction of the “Dalusian Library of Timbuktu” was completed, which houses more than 3,000 volumes of manuscripts from the 15th and 16th centuries. We can conclude this historical tour of the “City of 333 Saints” with a 15th-century Malian proverb: “Salt comes from the north, gold from the south, but the word of God and the treasures of wisdom can only be found in Timbuktu”. (Juan José Osés/Africana) – (123rf)