Thousands of children are deprived of a future in the cobalt mines of the Congo. The commitment of a group of Sisters is giving them hope.

Denise feels her way down the stony slope. Close to a huge mine runs a stream. The ten-year-old girl looks around shyly. Women immerse themselves in muddy brown water up to their ankles or even knees. They are sifting through stones that their children have previously collected from the creek bed and hauled down to them in heavy buckets.

Some of the pieces on the sieve glow a toxic green, others are adorned with a blackish-grey texture. Denise knows they’re trace amounts of copper and cobalt, making them both valuable. Stopping for a while, she sees what she now knows all too well. Children digging in the rubble. Women who can barely bend their backs. Little girls putting the ‘good’ stones into the bags. Denise hates everything about this place.

She knows all about this work and was once part of it. From early morning, while the sun was rising and at noon when she and her mother felt it burning relentlessly on their faces until the evening when they trudged exhausted to their mud hut home where they often fell asleep hungry, despite having toiled all day.

We are on the outskirts of Kolwezi, the capital of Lualaba Province, a dusty city of 600,000 people in the southeast of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Like Denise, a thousand children are forced to dig and extract that coveted material, cobalt, so much in demand.

The paradox is that although the land below Kolwezi is filled with riches, the people remain desperately poor. Their land is being robbed before their eyes. The world’s largest deposit of cobalt, an urgently needed mineral for the batteries of computers, smartphones, and electric cars, could be a blessing for Kolwezi – if it hadn’t become its curse.

The next day, Denise woke up at five in the morning, washed in front of the hut, put on her red sweater with its Mickey Mouse picture and walks through the narrow streets of the neighbourhood with her backpack. There are yellow cans everywhere. They are used to carry water because there are no wells nearby and even if there were, the water would be too polluted because of the mines.

Denise walks happily along. She is allowed to go to school for two years. After three-quarters of an hour’s walk, she arrives at Kanina, a large building where several children are already playing in the courtyard. Denise joins in and if it weren’t for her red sweater, she would hardly be noticed in all the commotion. Then the bell rings and she runs with the others towards her class.

On the first floor, Sister Jane Wainoi tells us: “There are 1,000 children in this school alone. And they have all had a terrible time in the informal mines”. Sister Jane is part of the congregation of the Sisters of Our Lady of Charity of the Good Shepherd. It is the story of a now indissoluble bond between this congregation founded in France in 1835 by Saint Maria Euphrasia Pelletier and present in about seventy countries, and the ‘cobalt people’, i.e., hundreds of thousands of individuals – at least a third of whom, children aged up to 7 years – are exploited in the mines of the province of Lualaba, formerly Katanga, in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

When the Sisters of the Good Shepherd arrived in Kolwezi a full ten years ago, invited by the Bishop of Kolwezi, who was concerned about children, they were shocked by the exploitation and poverty. “There was a public school for a few hundred children from wealthy families, nothing else. The children are income generators for many of the parents here. They have to help dig cobalt simply because there is no choice: shovelling is the only way for most of them to get some money. The only other option would be starvation”.

So, the Sisters set to work. “The idea from the beginning was that the children here should feel they are loved, not just by us but by God. They should also have affection and security and, of course, enough to eat”, says Sr. Jane. In a short time, kitchens were built to prepare large pots of food cooked over fires. The main food is bukari, the typical Congolese cassava-based porridge, eaten with lots of cooked vegetables. For Denise and most of the children, it is usually their first and only meal of the day.

While living among these children, it is easy to hear their stories. First, the little ones, who previously only knew how to collect cobalt scraps. And then the older ones, who had gone down the wells and had found themselves in a real hell. “We were 20, maybe 25 meters deep”, says Yannick. “There were no safety measures at all. We dug for cobalt all night long”.

In the morning, after digging all night, the sacks full of cobalt pieces went to intermediaries who resold them. Yannick tells us, “I watched as parts of the tunnel collapsed with men dying in the process, and we continued to hammer our pickaxes into the rock for hours with the dead lying there behind us.”

Without the Sisters’ help, Yannick would probably have died in one of the wells or would still be digging down there. But one day, a woman dressed in blue pulled him out of that hell. He is now attending school and his ambition is to become a computer technician.

What the Sisters have created in recent years is much more than just a school. From scratch, they built a total of seven more schools in and around Kolwezi with the help of donations and foundations. They created a programme to help resolve conflicts that had reached Kolwezi through cobalt fever. Lured by the deceptive prospect of quick wealth, members of completely different ethnic groups came to the city and violence often broke out. In a vocational school run by Sisters, girls who have suffered the worst abuse from gold miners also find help.

The Sisters are not approved of by many ‘businessmen’ who do not like to lose children as cheap labour. To date, the Sisters have been able to rescue more than 3,000 children from the mines and place them in school.

Nor are the police and the Kolwezi authorities happy that the Sisters’ efforts are attracting international attention. “Many want us to leave or to shut up”, Sister Jane says. “We can’t. We want to be the voice of the silent, because what is happening in this place literally cries out to heaven. But it’s not enough to look and complain, something must be done for the people here”.

Today Sister Jane and her Sisters are trying to give a future to a place whose only perspective so far lay in the depths of the subsoil. “But it is not enough for the children to go to school”, says Sister Justicia, a young and lively Kenyan who has been in Kolwezi for three years. “It is equally important that parents get income in other ways, because otherwise, sooner or later, they will take their children out of school and go mining with them again”.

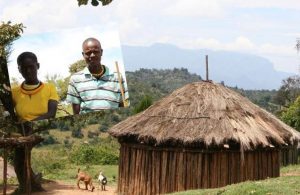

The Sisters not only denounce the sad reality of Kolwezi but have founded Chakuishi – translated, it means ‘food for life’. They have set up a farm just for women: 40 hectares of fields, 12 fishponds, and a micro-credit model that allows people to free themselves from exploitation.

Sister Jane proudly displays the bananas and beans, spinach, corn, and vegetables that grow in the fields, which are cultivated by the women. “They are the most vulnerable in the mines,” says Sister Jane, “but since most of them cannot read or write, so far, they had no alternative to cobalt. If we give them an alternative, we will also save their children. Starting with women makes sense because they are more responsible. They take it one step at a time and never lose sight of their goal”. (Von Christoph Lehermayr/Missio – Photo: Simon Kupferschmied)