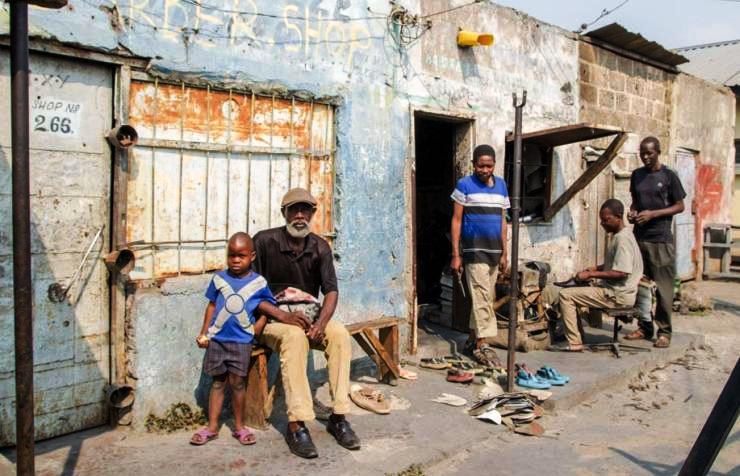

The slums surrounding the centre of Lusaka, the capital of Zambia, can be classified by their level of degradation. They are located just a few kilometres from the central shops and street stalls. Dirty roads and houses without drinking water: this is what one can see in the suburbs of George and Lilanda, and the high population density makes coexistence even more difficult.

An intense wind lifts up reddish soil grains and passers-by have to cover their eyes while advancing along the familiar roads. The chaotic structure of the streets causes the formation of small eddies at some street corners, which complicate visibility even more. “This wind can sometimes be rather annoying and besides, it covers everything with dust”, says Chareoes, an electrician who has been working on his own since the country’s official company stopped hiring a few years ago.

We start our walk through the slum early in the morning. The people living in this place start their activities at dawn. “You have to take advantage of daylight hours to consume as little electricity as possible. Daily tasks such as going to the public fountains to fill water tanks, because there is no drinking water in the houses, or making craft beer or exchanging products, are all activities that are done in the morning, there is no time to lose”, Chareoes adds.

The shop owners sprinkle water on the ground so that dust does not enter their stores. Almost no one wears masks to protect themselves from COVID-19 in the neighbourhoods of Lilanda and George – only 3% of the population of Zambia have been vaccinated – but the wind forces them to put any random piece of cloth or the upper part of a t-shirt over their nose and mouth.

Chareoes, a father of four, explains that one can see many children in the streets of these slums because they cannot attend school since their families cannot afford the monthly tuition fee of 60 kuachas (about three and a half euros) required by public or community schools. “People, here, live day by day and with what they manage to scrape up, they can hardly get any other thing that is not food”.

For this reason, the presence of ubuntu, the traditional philosophy of Zulu and Xhosa origin that carries a fairly broad English definition of ‘a quality that includes the essential human virtues of compassion and humanity’, is still widely referenced in these realities. Nelson Mandela, South Africa’s first democratically elected president, encapsulated the many interpretations of this word by calling ubuntu an African concept that means “the profound sense that we are human only through the humanity of others; that if we are to accomplish anything in this world, it will in equal measure be due to the work and achievements of others”.

The ubuntu concept, which is an alternative to individualistic and utilitarian philosophies that tend to dominate in the West, and which could be briefly sum up with a short sentence: ‘I am because we are’, is a real necessity in the townships or poor suburbs of Lusaka. Here, everybody tries to contribute by putting together the little they have when there is one of them who needs to buy something or pay off a debt. The people here are committed to helping each other.

Women are usually in charge of the rudimentary machines to make craft beer which is obtained by mashing corn. This process requires time since the machines do not work properly and sometimes you must wait for hours before obtaining the liquid which is then left to ferment.

Alcoholic beverages are sold in large quantities in these suburbs, stores are packed with bottles of beer and spirits, and posters on the walls invite customers to drink. The prices of alcoholic beverages are much more affordable than basic food products on the market. The easy access to alcohol, which is cheap, has favoured alcohol abuse. Alcoholism has become a serious social problem, which has also a major impact on the increase in domestic violence against women. “Men often start drinking early in the morning, they drink to relax and forget their problems, and when they get drunk they often become extremely aggressive”, continues Chareoes.

The abandoned objects littering the streets become the toys with which the children of the slums play during the day. Nobody watches them, they take care of each other. The one who is five years old feels responsible for the younger ones; for instance, he makes sure that there are no cars when the younger ones cross a street, or that they do not move too far from the door of their house.

The apparent carelessness of mothers is justified by the daily tasks they must accomplish in order to ensure at least one meal a day. Everything is more difficult when you are poor. You have to ration the little food available: small quantities of fruit, vegetables, and dried fish.

The traffic in the streets increases throughout the morning. The vans transporting people from one suburb to another clog the main streets and cause traffic jams. Nevertheless, nobody loses their temper; after a long wait you may see a driver berating another because he is blocking the street, but nothing more than this, as the patience of the inhabitants of these slums, is immense.

“There are different levels of poverty in the suburbs or townships of Zambia”, says Chareoes. For instance, there are significant differences between the neighbourhoods of Lilanda and George, though they are just separated by a paved street. The streets of Lilanda, where most of the inhabitants can afford paying basic services such as garbage collection, are relatively clean and there are no deep holes that turn into quagmires when it rains; while in the George neighbourhood, where its small houses are attached to each other, there are piles of garbage at street corners. There have been several cholera outbreaks in the area.

“We try to live our lives the best we can, but the cost of living is very high in Zambia, and with the little money we make we cannot afford to buy basic products. Survival here is difficult, but we try to go on”, says Chareoes. He tries not to lose hope and is convinced that education is the only way out of poverty. Those families like that of Chareoes, who are aware that a better life can be achieved thanks to education, do their best in order to afford tuition for their children, whose only fault was being born in a place without resources.