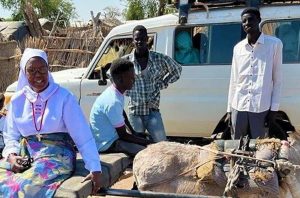

A meeting to seek concrete solutions to problems and, most of all, to get to know one another. A Catholic nun livens up the proceedings.

Room has run out in the convent hall. People are talking loudly. We exchange greetings. In the end there will be 350 people here including imams, village chiefs and the Sultan himself along with his guards who are all sporting red outfits.

Once a year the representatives of the twelve villages gather to discuss various issues at the convent in Tibiri, a town located just eight kilometres from Niger’s third largest city of Maradi. Sister Marie Catherine Kingbo came up with the idea of the gathering six years ago. She told us: “We started talking about family, health, and issues affecting the various villages.”

“This Saturday we shall discuss circumcision, forced marriage, and polygamy – delicate subjects in a Muslim patriarchal society, where the number of wives a man has contributes significantly to his reputation. Men consider polygamy as part of a tradition, deriving from the Qur’an itself.”

Sister Marie Catherine is Senegalese. In 1976, she joined the Filles du Saint Coeur de Marie congregation, taking her vows in 1978. She immediately joined the group of young nuns. Over the years, she also assumed international responsibilities. In 1990 she was elected President of the Union of Superiors General of Senegal. In 1995, she became Vice President of the Union of Indigenous Superiors in West Africa. In 2000, she was appointed Honorary President of the Association of Superiors General of Francophone Africa and Madagascar.

After her mandate, she returned home to train young nuns. Then, in 2005, the Bishop from Maradi’s new diocese asked her to travel to the Republic of Niger and help establish the foundations of a women’s order in his diocese. On October 22, 2006, the “Fraternité des Servantes du Christ” congregation was born, which is especially active with women, children, youth and families in general. It promptly tackled social work in the villages around Maradi. Today, Mother Marie Catherine is the Congregation’s Superior, which also includes five sisters, six novices and seven postulants. The Fraternité is made up of six different African nationalities.

Niger is one of the poorest countries in the world. Nine million – out of a population of 22 million – live in conditions of extreme poverty. There is no sign of improvement in the near future. The West African monsoon used to bring sufficient rain from May to October, but it’s become increasingly rare, and people are suffering ever more drought and famine. Many barns empty out before the next harvest.

“Less than one percent of approximately 11 million inhabitants within the diocese of Maradi’s jurisdiction are Christians,” said 70-year old Bishop Ambroise Ouédraogo. To date, he’s the first and only bishop of Maradi, one of the two in Niger (the other being in Niamey, the capital).

At the convent, Sister Marie Catherine opens the proceedings: “Today we want to discuss what prevents Niger from developing.” She notes the slavery and monoculture that the French imposed on the populations. The audience nods in acknowledgement. Everyone agrees that Niger continues to suffer from the legacy of foreign domination. While the talk revolves around France’s responsibilities in hampering Niger’s development, many also attribute blame to local politicians.

Sister Marie Catherine then introduces the first ‘delicate’ issue of the event: female circumcision – a centuries-old and cruel tradition, which remains widespread in rural areas, often causing lifelong health problems for those affected. The atmosphere becomes restless in the areas where the women sit. Most of them understand the problems of female circumcision all too well, given that they were themselves victims of forced circumcision, and often having daughters who have been subjected to the practice. Men follow events with still faces. They know what the women are talking about. The room becomes heavy with silence.

Sister Marie Catherine knows that she cannot take the subject too far. Yet she does not balk as she speaks about the sufferings that she heard directly from some girls. The following topic doesn’t lighten the atmosphere: it’s forced marriage. In Niger, not only does this often imply an involuntary union, it also can mean ten or twelve-year-old girls being married to men old enough to be their grandfathers. “We must fight against this and against early pregnancies,” insists Sister Marie Catherine.

The Sultan of Tibiri, Abdou Balla Marafa, strongly supports Sister Marie Catherine’s efforts. He is the head of the Goubur, a people which migrated from the Middle East and which has always fled from armed conflicts in Niger. Abdou Balla Marafa expresses concern over Niger’s growing problems from food insecurity and the cholera outbreak during the last rainy season, to the threat of Islamic fundamentalists. “There are great sources of tension. Boko Haram fighters from neighbouring Mali and Chad are invading border areas, looting houses, kidnapping children and extorting ransom money.”

Last January, Mohamed Ibn Chambas head of the United Nations Office for West Africa and the Sahel (UNOWAS), addressed the UN Security Council, noting that 4,000 people were killed in jihadist attacks in Niger, Burkina Faso and Mali in 2019, compared to 770 deaths in 2016. The number of internally displaced persons in these three countries has also increased tenfold to around half a million.

The attackers have frequently targeted the local Christian community. Catholic leaders denounced the attackers’ demands that Christians “convert to Islam and renounce their faith, not to mention the fact they destroy and desecrate Christian religious symbols.”

For some years, the police have maintained a presence near the Tiburi nuns’ convent. Because of the repeated attacks against believers, the Catholic community of Maradi arranged to have a wall built around the cathedral grounds. Father Pierluigi Maccalli, of the Society of African Missions (SMA), in the mission of Bamoanga, was kidnapped in the night between September 17 and 18 and remains in captivity.

Sultan Abdou Balla fears that Islam in Niger, which has typically been liberal, could become radicalized. He believes that “mutual rapprochement, respect, knowledge and understanding of the other” are the finest weapons to fight against extremism – and these are the very tools used by Sister Marie Catherine. This is one important reason why the Sultan backs Sister Marie Catherine’s initiatives.

During her events, Sister Marie Catherine, for whom humility is an important part of her spirituality and part of her service to the poor, tries to spark mutual understandings between Christians and Muslims. Breaking the prejudices, attitudes and traditions that have been rooted in people’s minds for generations takes patience, empathy and often moderation.

During the event, a man insists that the woman must take care of the home and family and has that Sister Marie Catherine has no business in society. He points out that Islam assigns her this role because she is not educated. A village chief wants to quote a surah from the Koran that confirms what the Imam stated. However, he did not expect Sister Marie Catherine to contradict him: “I have done many studies on Islam,” she said, “but I have never encountered a surah that forbids women from leaving home.” And then, a well-dressed and eloquent young woman interjected. She was puzzled and noted that many men fail to look after their wives, as the Koran demands. Meanwhile, a man asked: “How can a woman stay in a house where there is nothing to eat or drink?” While the girl receives a loud applause, Sister Marie Catherine observes: “These gatherings are great opportunities for women. Here they say what they think, at home they would not dare to.”

Meanwhile, apart from discussions of the problems, some offer possible solutions. Women insist that jobs must be created to halt the migration of youth and their husbands. Men speak about the need for more fertilizers for their fields. Time runs fast, but many get the chance to discuss their ideas and present their requests. The 80-year-old Ibrahim Moussa, who attended the gathering for the first time, said: “I think it is good that Christians and Muslims are sitting here under the same roof. We share the same values because we have the same God.”

(Beatrix Gramlich)