It is the largest and the most important. The monastery concentrates certain original characteristics that do not occur in others.

In the first place, its antiquity. Founded by Aregawi, one of the ‘Nine Saints’, at the beginning of the 6th century, it is at least as old as those founded by his fellow monks, such as that of Pentelewon in Axum, Afse in Yeha, Gerima in Medera or Jim’ata in Geralta. But, should the monastery not be the oldest in Ethiopia, what is generally admitted is that the church of Debre Damo is the oldest now existing in the country.

According to tradition, it belongs to the time of Emperor Gebre Meskel, son and successor of Kaleb, during the first half of the 6th century, while Aregawi was still alive. Even though it was destroyed and rebuilt more than once, it has kept the original form and is the only existing proof of Aksumite art. In spite of its apparent rusticity, it is a work of perfect harmony. The perimeter of the building is rectangular. Its walls alternate layers of stone and wood, which break up the monotony and create a soft contrast of light and shadow. Also of great beauty is the ceiling, consisting of wooden coffers on which numerous animal and plant figures are engraved. Its connection to the Aksumite architecture is obvious. For instance, the shape of its doors and windows can also be seen in the reliefs on Aksum’s obelisks.

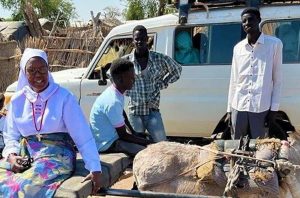

The second characteristic is its picturesque location. Debre Damo is an oval-shaped flat-top plateau, rising up 17 meters from the surrounding landscape and measuring one kilometre in length and a half in width. The bare rock walls drop off steeply on all sides, being accessible only by using the ropes that the monks throw from the top. Tied to them, the visitor is lifted up. Sensations, not all of them pleasant, take hold of him as he climbs up, and even more so, when it is time to go down. Vertigo is one of those sensations, as one dangles off a 17 meter-high cliff. No female presence, not even that of female goats or sheep, is allowed to the holy mountain.

One question arises then: if today it is the monks who throw the rope down to anyone who wants to climb up, who did it for the old Aregawi, the founder of the monastery? Tradition provides an answer to this question. Before Christianity arrived, there was a snake, worshipped by the locals, dwelling on the rock. It was this snake that, in an attempt to kill the holy monk, first helped him up the mountain but, once on top, hurled him violently to the place where the church stands today. The numerous and varied paintings depicting this scene always portray Archangel Michael with his sword raised, deterring the snake from hurting the Saint.

Despite its geographical isolation and difficult access, Debre Damo was very influential throughout history. The emperors through the Middle Ages tried to keep control of it by nominating its abbots. In the 13th century, Iyasu Mo’a and Tekle Haimanot, the future founders of the two great monasteries of Hayk and Debre Libanos, were educated in Debre Damo by the Abbot Yohanni. In the 16th century, when the Muslim leader Aḥmad Grañ began sacking and burning throughout the nation, Emperor Lebna Dengel took refuge in Debre Damo and died there. It was at that both tragic and glorious moment in history that, for the first and the last time ever, the rigid rule forbidding women to climb up the mountain was broken, because it was there that Lebna Dengel’s widow Seble-Wengel welcomed the Portuguese soldiers who had come to the nation’s rescue. It was there that she ‘wisely and cautiously’, according to the Portuguese chronicles, planned the armed resistance against Grañ and it was there that she finally received the news of the decisive victory over him. Debre Damo is, in fact, one of the very few places throughout the Christian empire that escaped the destructive fury of the Muslim Conqueror Ahmed Grañ.

Starting from the 17th century, however, the monastery lost much of its primitive splendor and influence. Talking today with any of the monks living in Debre Damo produces a strange feeling. Their answers to the curios questions of the visitor may respond not so much to how things actually are as to how they should be according to what old traditions affirm. And some of their answers may differ from the reality the visitor can see with his own eyes. For instance, one of them states that the monastery, in all its past splendor, accommodated up to six thousand monks and that, even today, the monastery houses 200 monks and 150 young aspirants. But it is hard to imagine that this rocky and barren ground could house even those 350 people. In the monastery, they have no common life except daily prayers. At midday, they are supposed to meet for the Eucharist. It is now noon and the bell tolls but, out of the labyrinthine alleys, the visitor can see no more than a dozen monks emerging to gather.

Another monk deeply rejects the idea of sending monks from Debre Damo to be educated somewhere else. His viewpoint is that every monk has, in his inner life and in his communion with God, enough resources to feed his monastic life without seeking outside knowledge. Knowledge about the world – he affirms – does not help the monk. Logically enough, he is also against accepting adult vocations in the monastery, “because, in fact, they already know too much about the world”. For him, the ideal vocation is that of the young boy who joins the monastery before having worldly experiences. Even though his answers may not represent the opinion of all monks of Debre Damo, the fact is that boys – almost children – are the ones joining the monastic life. Adult vocations from any sector of society are rare, and even more so from among the educated class. Difficult to imagine today Debre Damo as a centre of learning as it is said it was in long past history.

Debre Damo used to possess abundant lands from which rent the monastery lived. But those times have been left behind, especially after the nationalisation of the land made by the revolutionary government of Mengistu Hailemariam in 1974. Today the few monks of the monastery live on the offerings of the faithful or the few tourists and from the little subsidy that the Ethiopian Orthodox Church passes them. (Juan Gonzáles Núñez)