The Turkana are a Nilotic people native to the Turkana District in northwest Kenya. The Turkana refer to themselves as “Ngiturkan” and their land as “Eturkan”. We look at some aspects of their life.

The climate is hot and dry for the most part of the year. The average rainfall is about 300-400mm, declining to less than 150mm in the arid central zones. There are two important rivers, the Turkwell and the Kerio, which flow into Lake Turkana, coming from the Kenya Highlands. They have water for four to six months of the year.

Women grow millet and sorghum, but the yields are poor and only supplement their diet to a minor degree. Along the Turkwell and the Kerio banks, more settled but less prosperous groups of Turkana grow wheat and maize in substantial quantities.

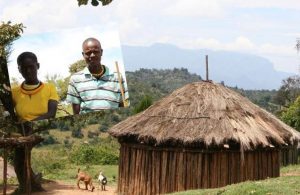

Turkana homesteads are temporary and mainly made of thorny boughs; in some areas, palm leaves are also used. To protect themselves from wild animals, mainly hyenas, they enclose their homesteads with a fence of brushwood boughs. Members of one family seldom live together. At the height of the dry season, a man may have up to three or four homesteads, one for the cattle and the sheep, one or two for the wife or wives, one for camels.

Traditional economy is based on livestock. Animals play an important role in the payment of the bride-wealth, in compensation for crimes, or in ‘gift offerings’ on social occasions. Cattle are so highly valued that the Turkanas often raid other ethnic groups to increase the number of their herds. And woe to those who tell them that they are stealing animals! They are just ‘taking the animals home’, since God gave all cattle to the Turkana. This truth demands that also other pastoralist groups think the same. Reciprocal raids are everyday business. In the old days, they were carried out with spears and arrows. Today, raiders use Kalashnikovs and the death toll is always dramatically high.

Three elements make up the world of the Turkana: human beings (ngitunga), animals (ngibaren) and Akuj (God). The animals, such as cattle, camels, goats, sheep and donkeys, are central to the political, economic and religious experience in their life. Cattle are highly regarded, and are only seldom slaughtered, since they provide milk, blood, skins, dung – used as fuel.

The Turkana use livestock to pay the bride-wealth, to celebrate initiation rites, and to make sacrifices. An animal is part of any important ritual, be it of joy or of sadness. At the death of a person, an animal of the same gender of the deceased is sacrificed, not before having consulted the emuron (diviner) on the characteristic it must have. A castrated animal can never be a sacrificial victim.

Animals play an important role in every step of a person’s development. It is by means of a sacrificed bull that a young man becomes an adult during the rites of initiation, thus getting the right to marry, create a family and join the elders in the guidance of the society. At initiation, a man takes the name of his favourite animal. After that, he praises and imitates it when singing and dancing, when going on a cattle raid and in daily conversation.

The possession of cattle makes man into a ‘superman’, almost as a ‘spirit’. After all, the forefathers have become ‘ancestors’ and in strict connection with the divine world through the ‘generosity’ they expressed towards animals by celebrating feasts and making ‘animal sacrifices’. A domestic animal reaches the apex of its ‘glory’ when it is chosen as a sacrificial victim.

A ‘domesticated’ animal is more than just an animal. Through its close relations with man, it becomes almost ‘human’. That is why a human easily identifies himself with an animal.

The livestock provides the identity of the human group, by defining its parameters and affinities, its genealogy and its political and economic activities. The animal, not the human, is the mark that shows the membership of a specific group.

In ‘forming’ the clan, the animals create and perpetuate the relations even between the living and dead members. They ‘belong’ to the clan whose brand they bear; in fact, they are the property of the ancestors as much as they are of the head of a family.

When social or personal relations are strained or break up, it is always an animal that ‘mediates’ the healing and the recreation of those relations. When the Turkana say that “livestock creates the home”, they really mean it.